Everyone has seen the transparent squiggles moving across the field of vision. What these squiggles are is protein, tiny pieces of it, found inside the eyeballs that are called floaters. If they bother you, you’ll like these news: science discovered method to safely remove these proteins by using laser technology.

You should know that this is not only getting rid of some small annoying dots, but the floaters may get larger and cause more problems with age. But another thing you should know is that they are actually harmless in general.

Boston scientists examined the impact of this laser treatment technology that is called YAG (Yttrium-Aluminum Garnet) laser vitreolysis in contract to a placebo treatment which the control group was exposed to.

This method has been tested some time before, but it is the first time that is used in comparison to placebo treatments, and the participants could imagine their improvements.

Based on the examination results, the improvement seems to be realistic: within the treated group, 54% of the participants reported vision improvement, in comparison to 9% in the control group treated with placebo.

The experiment included 52 volunteers, over a period of 6 months.

The group treated with the laser method reported higher improvement in the symptoms than the control group.

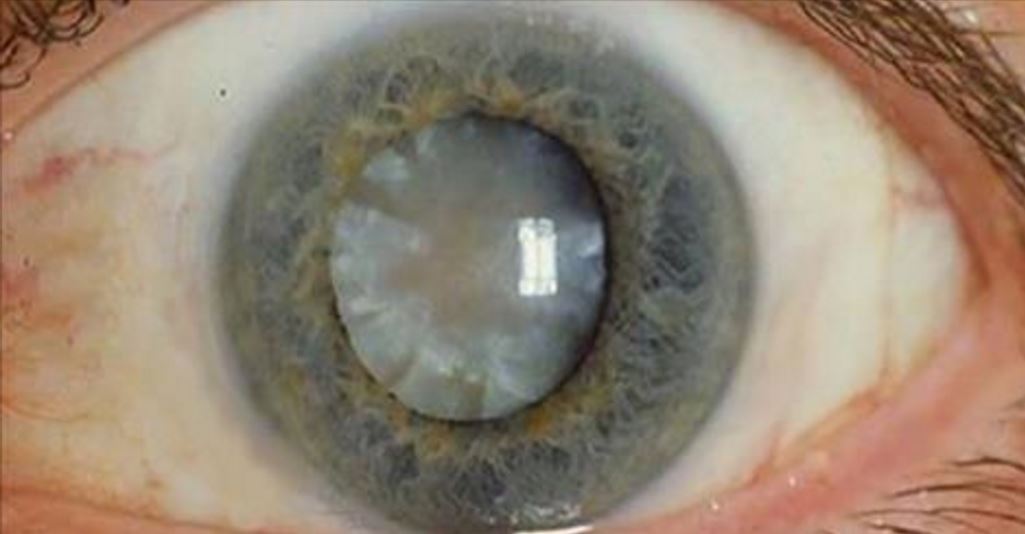

The medical term for these proteins is muscae volitantes in literal translation from Latin – flying flies. These appear when small pieces of either protein, a tissue or blood cells cast shadows on the retina tissue on the back of the eyes. How clearly you see them depends on the closeness to the retina.

Since they are suspended in the gel-like structure filling the eyeball, they seem as they are floating around and that is why they disappear when we make an attempt to stare at them.

With age, this gel-like structure (vitreous humour) may start falling apart and become more liquid which results in these floaters gluing together, creating larger clumps and knots. They may have a serious effect on vision.

What this method does is actually dividing these floaters into smaller pieces, with the help of a special contact lens made especially for this. The doctors directly aim at the floaters with a 6 microns wide target.

This process is pain-free and is not invasive and it is currently available to patients but there is still not sufficient information on how effective or how risky it actually is.

Scientists confirm that the small size of the sample and the short period of follow-up as the lack of other treatment options makes further studies necessary.

Still, at least there is some proof that patients undergoing the treatment are not only experiencing a placebo effect but are really seeing improvements in the vision.

Still, if you want to try the method it may be good to wait and see what the next studies will find out.